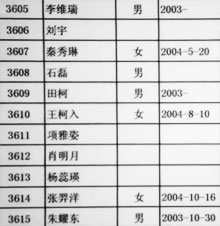

Art, Politics and Media in one gesture

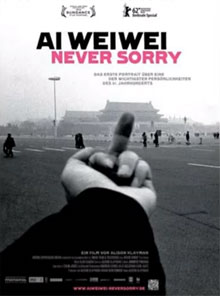

Detail of a still from the 91 minute documentary

“Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry” 2011 by Alison Klayman.

He is documenting for his blog in a Munich hospital after surgery for a brain hemorrhage during his ‘So Sorry’ show at Haus der Kunst. aiweiwei.blog.hausderkunst.de

The title of his exhibition,

‘So Sorry’ refers to the apologies expressed in the headlines of the news worldwide for a tragedy or wrong as if an apology meant it was too late

to make amends.

In this sense the title of the documentary could be read as meaning that Ai Weiwei is never sorry, never finished with seeking justice or freedom.

Detail of a photo from smarthistory.khanacademy.org of “Remembering” by Ai Weiwei was made out of 9000 children’s backpacks in five colours attached to the facade of the Munich, Haus der Kunst, between October 2009 and January 2010.

Still from the 2010 50 minute BBC documentary “Ai Weiwei, Without Fear or Favor”

on Youtube (06:50)

“She lived happily in this world for seven years”

was said by a mother of one of the victims of the 2008 earthquake.

Sitting in hospital here holding out his camera and giving the finger is Ai Weiwei at work as both art and activist. His extensive oeuvre as a conceptual artist inform those of us who choose to read this as art, that like Joseph Beuys and many others, intent makes this art. That the blog is hosted by the “Haus der Kunst” as one of the works in the show is the means for immediate access to the museum visitor. But there is another layer going on here. In China only officially approved blogs are allowed and twitter is often blocked by the government as are his blogs. So for a Chinese person to even engage in using twitter or any media (all publications are censored) not officially approved is an act of rebellion: hence the finger – as an aesthetic response and as act of defiance.

Still from the BBC documentary “Ai Weiwei, Without Fear or Favor” on Youtube (07:14).

About 100,000 people seemed to have disappeared without any trace or information. Over 7000 school buildings collapsed while the adjacent buildings remained intact.

When I first heard the publicity surrounding his hospitalization I found it over the top because of the focus on him and his health. Seeing the documentary gave me a context.

His continual badgering – his ongoing showing and telling is both a performative and tactical staging. The artist as activist who reveals, or the artist as human being wanting to live in a society where there is justice and freedom of expression.

The August 2009 beating in Chengdu also had artistic and political contexts. Ai Weiwei was there to provide evidence in support of Tan Zuoren on trial for “inciting subversion of state power” (More details are here) who was arrested 3 days after publicly releasing a report showing that over 5000 students had died as a result of shoddy school buildings which collapsed during the Sichuan earthquake in 2008.

Detail of a still from the 2010 BBC documentary “Ai Weiwei, Without Fear or Favor” on Youtube (08:04) showing a wall of names of the 5212 school children.

Ai Weiwei first visited the region in June 2008 because he wanted to use the names of the dead schoolchildren in an artwork to commemorate the tragedy and was told "The death toll is a secret" (2009 documentary "Hua Lian Ba Er" (Dirty Faces) by Ai Weiwei (Links to his videos)).

He found that children had been buried often without the parents being informed and the masses of school bags found in the rubble, often with their names removed, was the inspiration for his work "Remembering."

He used social media to ask for volunteers to help him to find out who these children were. Over 50 came to assist, knocking on doors in the towns and collecting the stories, and the names of the children who died due the collapse of school buildings. The numbers swelled to 5212.

Ai Weiwei posted these names on his blog on May 12th 2009 – the first birthday of their deaths. The Chinese government removed his blog two weeks later, and then a few days later blocked twitter across mainland China in anticipation of the 20th anniversary of the Tienanmen Square upheaval.

In another country it would be a poetic gesture: the naming of those children – but then in another country it would be another art work to start with because art exists in the contexts of its making and presentation. This commemorative act in this context became art of the unmasking.

His persistent documenting is a double-edged sword. His showing and telling – his own transparency – makes his both art and a human interest story to his thousands of followers, inspiring them to act as actors, participants or observers (some come to photograph). Is it less art if participants are drawn in to act? Less an artwork if it is also activism? Is it less worthy if it is also performative? His work here is art as a story told and activism as managed by an artist.

His use of social media is a way to communicate with his fellow citizens as much as a for medium for expression. And each time his access to his blog or to twitter is blocked, like many of the youth, he finds another way to communicate: all thanks to Tim Berners-Lee for keeping the web open to all and to the ubiquitous nature of the digital. However less than three percent of Chinese citizens are able to get around the “Great Firewall” (“Ai Weiwei and the Art of Protest” by Danielle Allen) which censors much of the internet in China.

“Eight months after the beating, he returned to Chengdu to file an official complaint and request an investigation. Several months later, having seen no action, he returned again to Chengdu with the strategy of filing requests for a hearing in as many government offices as possible. This series of encounters with government officials—nervous, bored, perfunctory, violent—is one of the film’s most powerful segments, and also one that Ai has broadcast via Twitter.

Still from the seven minute

TED talk: “Ai Weiwei detained” on Youtube at 5 min, 4 Apr 2011

In 2007 for his participation in “Documenta” in Kassel he created “Fairytale, ” the opportunity for 1001 Chinese citizens to travel to Germany, organized solely via the internet.

It was a journey not only to expose them to another culture and country but also to the power of social media, and their presence and experiences became part of the documenta exhibition as much as having an affect the documenta public. It was the largest project ever created for the documenta.

Will Ai Weiwei’s efforts make any difference? He is an artist whose work of petitioning is straightforwardly political, but whose use of the blogosphere to publicize that petitioning is artistic and political at once. But what exactly is the relation between voice as expression—the artist’s voice—and voice as influence: the citizen’s voice? And do social media change that relationship?”

(“Ai Weiwei and the Art of Protest” by Danielle Allen)

“Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” 1995, detail of a still from the 2010 50 minute BBC documentary “Ai Weiwei, Without Fear or Favor”

on Youtube (31:48)

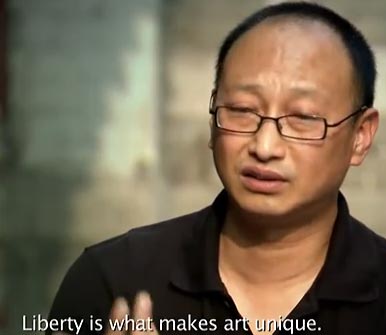

Detail of a still from the 2010 50 minute BBC documentary

“Ai Weiwei, Without Fear or Favor”

on Youtube (34:55)

“Liberty is what makes art unique” – Feng Boyi,

curator and art critic based in Beijing.

While there is a short introduction to his conceptual works, the documentary “Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry” tends to focus on him as an activist. There were aspects of his personal life shown that most would have kept out such as his out of wedlock child and the scenes with his mother who didn’t like what he was doing. You also see him as being silly and sometimes overzealous – being fallible and human. Perhaps this is a good thing since there is already an excellent documentry produced by the BBC in 2010 (you can watch it online here) which focusses on him as an artist.

And for someone immersed in the art world as I am Klayman’s human interest approach didn’t stop me from reading his blogging, videos, actions, and his silence at the end of the documentary as an ongoing work of art.

Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, a 91 minute documentary, produced by Alison Klayman and Adam Schlesinger, toured film festivals around the world in 2012 winning a number of prizes.

Links: 4 minute trailer Youtube

Vimeo page with a trailer

and related information

Official website

The DVD will be available

from Amazon from 4 Dec 20102

iTunes

@awwneversorry

A United Expression Media presentation in association with Muse Film and Television. Produced by Alison Klayman, Adam Schlesinger. Executive producers, Karl Katz, Julie Goldman, Andrew Cohen. Directed by Alison Klayman.

With: Ai Dan, Ai Lao, Ai Weiwei, Lee Ambrozy, Danqing, Ethan Cohen, Feng Boyi, Gao Ying, Gu Changwei, He Yunchang, Hsieh Tehching, Huang Kankan. (English, Mandarin dialogue)

Still from the Youtube video, Gangnam Style, first published on 24 October 2012. 55-year-old Ai Weiwei dances ‘Gangnam Style’ by to the South Korean rapper Psy’s song

The documentary begins with his 50 or more cats and while Klayman focussed on the one in a million cat who was clever enough to open the door by jumping against the handle I interpreted the overkill of domestic cats as a form of tactical aesthetics. Like giving the finger – an infantile gesture – the artist has far too many cats (too much of anything changes things), but there is another layer of meaning in the Chinese context. Maya Eva Gunst Rudolph wrote on her blog: “Deng Xiaoping’s famous declaration that “it makes no difference if a cat is black or white as long as it catches mice.” So much of Ai Weiwei’s work and life is devoted to wading through the black and white of ethical and political behavior, not to mention tangling with the often indiscriminate “mouse-catching” of the Chinese government” (Review: Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry By Maya Eva Gunst Rudolph)

Ai Weiwei has so many cats that it is satire or theatre (art at play).

Ai Weiwei’s latest video clip (released on youtube on 24 Oct 2012) of himself dancing “Gangnam Style” is another example of an art-life-act that runs in many directions. Someone who loves the South Korean rap artist PSY’s song which went viral in July 2012 will see this as poking fun at a hero. For another it is poking fun at oneself – an overweight middle-aged man who looks more like he is having fun exercising than dancing. It shows you don’t need to be beautiful to do something. For another it is poking fun at the meme: the latest trend. And artist Anish Kapoor has picked up on this as well, although he stated that he made the video in response to the Chinese government’s blocking of Ai Weiwei’s video.

“Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads” by Ai Weiwei, shown at Somerset House, London, 12 May 2011 – 26 June 2011. Photo by Sonja van Kerkhoff, which may be freely used if credited.

“Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads” by Ai Weiwei, shown at Somerset House, London, 12 May 2011 – 26 June 2011. Photo by Sonja van Kerkhoff (Creative Commons).

Free use if credited.

Detail of one of 12 statues which are a recreation of those made for the European-style Yuanmingyuan gardens, the old Summer Palace in Beijing which was destroyed by British and French troops 150 years ago during the Second Opium War. These statues were designed in the 18th century by two European Jesuits serving in the court of the Qing dynasty Emperor Qianlong. In re-interpreting these objects on an oversized scale, Ai Weiwei focuses attention on themes around looting, repatriation, the ‘fake’ and the copy in relation to the original or antique, culture and tradition. See: somersethouse.org.uk www.zodiacheads.com or

For the art world it pokes fun at the art of refinement or perhaps the slickly-made music video – his video is like a home movie where he and his studio assistants walk outside his house to perform for the camera which wobbles here and there, while waving dried leaves and handcuffs around. The shots of horses in stables appear suddenly and are gone again as if they were a mistake someone forgot to remove before the final cut.

Ai Weiwei employs artisans of the highest level when he wants to and his work is characterized by its attention to detail so anyone in the art world knows that the video “style” is a deliberate gesture.

For a Chinese viewer the horses in the stalls also poke fun at censorship. The Mandarin phrase ‘cào ni ma’ (grass mud horse) a mythical creature also means ‘fuck your mother’ and since 2009 has been widely used as word play in response to the censorship on the use of words on the internet in China (the characters used to write its name are benign and so remained undetected by the digital filters).

Words can be censored but meaning and thinking are as uncontrollable as a herd of cats. So it makes sense that when freedom of speech is controlled words have to be wordplay and gestures thrust the forbidden meanings into the public space.