“Rip, Shit & Bust – a response to invasive mining realities,” is the first exhibition in the recently renovated 1936 Kings Theatre just down from the Hundertwasser public toilets on the main street in Kawakawa in the north of Aotearoa | New Zealand.

Many of the paintings, prints, ceramics, raranga (flax weaving), carvings, sculpture and installations by the 17 artists relate to the exhibition theme of concern about drilling or mining: heightened naturally, by the recently begun Statoil oil exploration along the Northland coast. “Orificia Coffee Table” by Kaikohe artist Sash is a flashing glitter display case at shin height. The viewer has to adjust their stance and focus before the ‘blue worm’ which threads through the multiple eyes of Papatuanuku (Mother Earth) is recognized. The gentle flashing light works both as warning and metaphor for the flux of the natural world. Masks hide and reveal: here they represent a multi-eyed essence that is open and vulnerable. In Sash’s other work, “Don’t Go Chasing Waterfalls” an oil like ooze in continual flow, cascades over brightly painted and glittered rocks and texts.

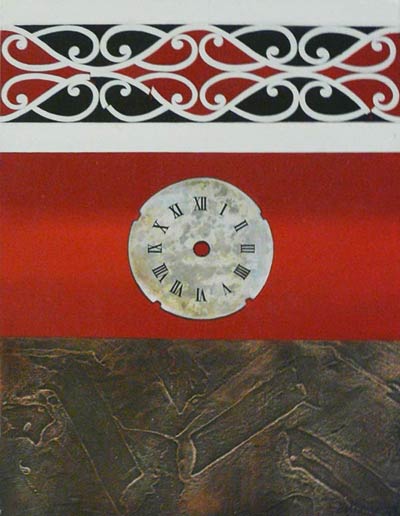

Theresa Reihana’s paintings and prints address the theme of the environment in more painterly terms. One of her paintings, pictured above, shows a fracture in the kowhaikowhai pattern above a clock face from a bygone age. The broken up earth below is almost abstract. The three divisions are like three worlds: the future (spiritual, conceptual or material consequences, with a fault line in the pattern of the universe), the present (time undefined) and the past (what has been done to the earth).

Each of the “Whenua” works by Theresa Reihana consists of two parts, the large face and a baby in a fetal position. Here “Whenua” is a powerful metaphor for what is missing between the two (in the Māori language whenua means umbilical chord). The gouged and ripped layers in plywood in the ‘earth mother’ indicate something is amiss, while the baby (each of us) floats disconnected.

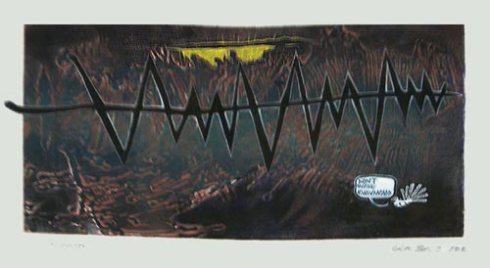

The print “Fossil Fuel” by Gabrielle Belz is a playful reminder that resources are finite and part of an ecosystem. Some of her other prints, such as in “Kia Tupato” (Be Careful), have drawings or cartoons on plastic laid on top of the print.

The text in this work reads “Don’t wake Ruamoko,” a reference to the guardian or cause of earthquakes. Her other prints also warn of unnatural disasters as a result of mining or drilling and Bev Wilson’s painting below addresses the same topic.

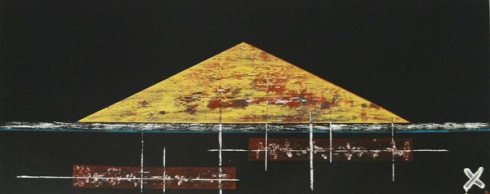

“There’s a Frac/tion Too Much Friction (as Tim Finn

would say) yeah” acrylic on board, copper-coated nails, by Bev Wilson

Under the mountain red breaks out around fractures and intrusions, like wounds that are irritated.

Raranga by Te Hemoata Henare consists of two 4 metre woven flax strips. A maro (a traditional apron or loin cloth that covers the pubic area) hangs in the middle flanked first by mountain patterns and then by river-like patterns. For a Māori person, acknowledging your mountain and river always comes before any mention of ancestry, so that identity is symbolically situated in connection with the natural world. The title refers to the technique and medium she has used but it could imply that the land or the natural world – the blank horizon above – is continuous and enduring. In the text about her work she refers to the whakatauākī (proverb), “Whatu ngarongaro te tangata, Toitu te whenua” (People perish but the land remains).

What makes this exhibition curated by Lau’rell Pratt and Theresa Reihana so stimulating is the diversity of media and styles and approaches.

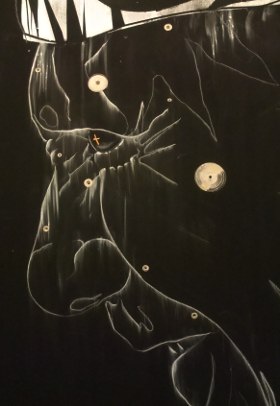

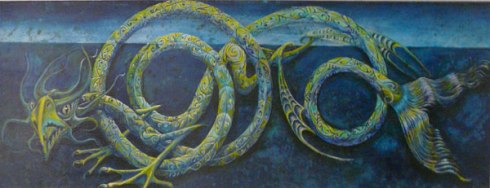

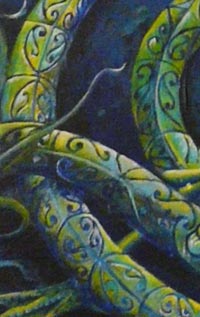

Julien Atkinson’s five large canvases are exquisite, not just because of his fine use of colour and technique but in their fine balance between design, technique and the conceptual. From a conceptual perspective, the manaia, a hybrid guardian of spiritual and material worlds, stands as if about to pounce on us, should we dare to approach. This stunning creature, the manaia, perhaps mythical, or perhaps not if only we had eyes to see, stands there to protect the land. Through the body we can see a horizon – the land this creature is guarding. In terms of design and technique: there is a beautiful play between flat decoration and three dimensional illusion, and Celtic and Maori stylistic features, along with sci-fi or hyper-realism.

“Ruru” by Tinike Hohaia, like Julien Atkinson’s paintings, is a celebration of creation combining the decorative with the painterly. Ruru, Māori for a native owl (The morepork, Ninox novaeseelandiae) is associated with the spirit world in Māori mythology. It is believed that if a morepork sits conspicuously nearby or enters a house there will be a death in the family, and so like the manaia, this work could be read as a warning. In some traditions the ancestral spirit of a family group can take the form of an owl, known as Hine-ruru, the ‘owl woman.’ These owl spirits can act as kaitiaki (guardians) with the power to protect, warn and advise.

Tinike Hohaia is one of nine artists in this exhibition who were students of Theresa Reihana’s marae noho (live-in workshops in a Māori setting) coordinated through the Northland branch of Te Wānanga o Aotearoa (a nationwide Māori educational foundation whose courses range from beginners’ to university level). Some of the artists, such as the kuia (Māori elder) Nellie Para, another of Theresa’s students, are exhibiting for the first time.Here Nellie Para has appropriated a photograph on canvas of the British actress, humanitarian, and fashion icon Audrey Hepburn (1929-1993) by giving her a moko (tattoo), a tīpare (a Māori style headband) and a whakakai (an earring), against a sky that reminds me of psychedelic art. I loved it that an iconic western image from a bygone time has been coloured by a local elder.

Fore: HiddenDestructionand Devastation, acylic on canvas, by Ann Hui, Orificia Coffee Table, glitter, masks, LED lights + show case plinth, by Sash.

Back: two paintings by Julien Atkinson, three paintings by Bev Wilson, two paintings and two prints by Maarie te Mamaeroa Jane Ruys, and five ceramic objects by Rhonda Halliday.

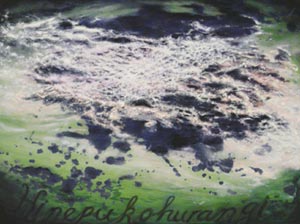

Hinepukohurangi, acrylic on canvas, by Natascha De Swart.

Artist statement: “The mist isa blanket for our landand rises as a blanketinourskyforourearth.”

Artists in the exhibition: Julien Atkinson, Gabrielle Belz, Graham ‘Tiny’ Dalton, Natasha De Swart, Rhonda Halliday, Te Hemoata Henare, Tinike Hohaia, Keatly Te Moananui Hopkins, Ann Hui, Keri Molloy, Kahu Reedy, Theresa Reihana, Maarie te Mamaeroa Jane Ruys, Sash, Alby Shortland, Nellie Para, Bev Wilson

The exhibition runs until January 20th 2015,

Kings Theatre, 80 Gillies St, Kawakawa.

Open daily: 10-4. Their facebook page.

This life-size copy of van Leyden’s 1526 triptych onto canvas (the original is around the corner

This life-size copy of van Leyden’s 1526 triptych onto canvas (the original is around the corner  Casper Faassen’s triptych, of the same dimensions, omits the figuration evident in Lakke’s. The central panel of frosted glass is illumined by a spot and the hinged two side panels are transparent sheets of glass. Is there nothing to say? Has it all been said? Has the story been removed or is it replaced with a new story? In any case what we are left with in Faassen’s work is an aesthetic of form bordering between high art and the domestic.

Casper Faassen’s triptych, of the same dimensions, omits the figuration evident in Lakke’s. The central panel of frosted glass is illumined by a spot and the hinged two side panels are transparent sheets of glass. Is there nothing to say? Has it all been said? Has the story been removed or is it replaced with a new story? In any case what we are left with in Faassen’s work is an aesthetic of form bordering between high art and the domestic. Some artists in the show responded to the themes of life and death, heaven and hell, or judgement such as Maayke Schuitema’s “Magna Mater”. Here a pregnant woman has replaced the crucifix and is flanked by scenes of women who are literally and symbollically juggling symbols of birth and death. Each woman’s womb bears either an symbol for life or death.

Some artists in the show responded to the themes of life and death, heaven and hell, or judgement such as Maayke Schuitema’s “Magna Mater”. Here a pregnant woman has replaced the crucifix and is flanked by scenes of women who are literally and symbollically juggling symbols of birth and death. Each woman’s womb bears either an symbol for life or death. Anyone familiar with contemporarty art can’t help but think of

Anyone familiar with contemporarty art can’t help but think of