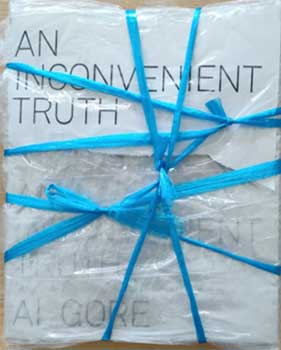

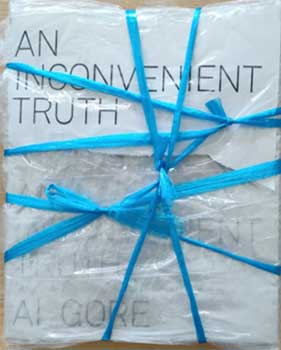

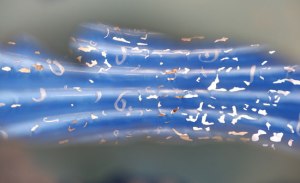

Detail of one of the ‘prepared’ books. Here Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth is given a Christo like wrap.

#oldmediahouse oldmediahouse more to come before 1 December 2024.

Old Media House oldmediahouse

Detail of one of the ‘prepared’ books. Here Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth is given a Christo like wrap.

#oldmediahouse oldmediahouse more to come before 1 December 2024.

Old Media House oldmediahouse

Tags: kaiparacoastsculpture, kaiparacoastsculpturegardens, oldmediahouse, tewhareaopapaho

Artists in Aotearoa | New Zealand are kaitiaki (stewards) for artists

in countries more stricken by COVID-19

Aodhán Floyd | April Shin | Ashleigh Taupaki | Bev Goodwin | Brenda Liddiard

Cathy Carter | Chiara Rubino | Emma Papadopoulos | Jessy Rahman | Jumaadi

Lipika Sen | Lissy and Rudi Robinson-Cole | Lloyd Lawrence | Michelle Mayn

Naomi Roche | Narjis Mirza | Martin Wohlwend | Masud Olufani

Nawruz Paguidopon | Prabhjyot Majithia | Phil Dadson

Pietertje van Splunter Robert Hamilton | Sen McGlinn | Shaeron Caton Rose

Sonja van Kerkhoff | Ursula Christel | Xiaojie Zheng | Yllwbro

Detail – Metamorfosi, 2021, Chiara Rubino (Matera, Italy) and Cathy Carter (Auckland, NZ)

Archival pigment ink photographic print on Hahnemuhle photo rag 306gsm. 140 x 90 cm.

Two more works in the main gallery. More photos on artsdiary.co.nz

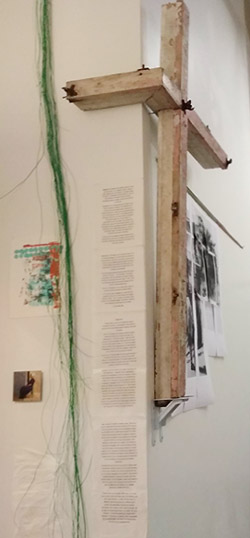

Left of doorway: Planetscape by Lloyd Lawrence (NYC, USA) and Sonja van Kerkhoff,

The Shaman and the Healing Tree (with mirror) by Jessy Rahman (NL) and Sonja van Kerkhoff.

Metro Manila, photo-print by Nawruz Paguidopon

Above: A Paradox of Place by Sonja van Kerkhoff. Acrylic on wood, 61 x 84 cm. Wood from the Netherlands with a view of Matariki (The Seven Sisters constellation) as above Aotearoa.

Earthscape I, II, III, by Lloyd Lawrence (NYC, USA) with Sonja van Kerkhoff, 3 laser prints on transparency. Limited Edition of 5. Approx 29 x 20 cm. Lloyd emailed photos of his colleges made out of Art Catalogues, giving Sonja freedom to print them in any manner.

Diary of Dust, 2016, Animated, Produced, and Directed by Dave Brown. 2 min 53 sec animation featuring Jumaadi’s, 2014, 7 metre drawing made during a residency at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, College of Charleston School of the Arts, South Carolina, U.S.A. The Halsey Institute commissioned San Francisco-based filmmaker Dave Brown to make this video animation with original gamelan music, composed and performed by Nathan Koc.

Philoxenia 4, 2021, by Emma Papadopoulos. Acrylic on paper, 24 x 30 cm

Josephine’s Mother by Sonja van Kerkhoff, photo-print, 10 x 10 cm, crushed paper – Naomi Roche.

Detail of the main gallery – works by Aodhán Floyd (Cork, Ireland), April Shin, Brenda Liddiard, Jumaadi (Australia/Indonesia), Emma Papadopoulos (greece), Masud Olufani (USA) and Ursula Christel, Nawruz Paguidopon (The Philippines), Phil Dadson, Pietertje van Splunter (The Netherlands), Shaeron Caton Rose (UK), and Xiaojie Zheng (SF, USA/Wenzhou, China)

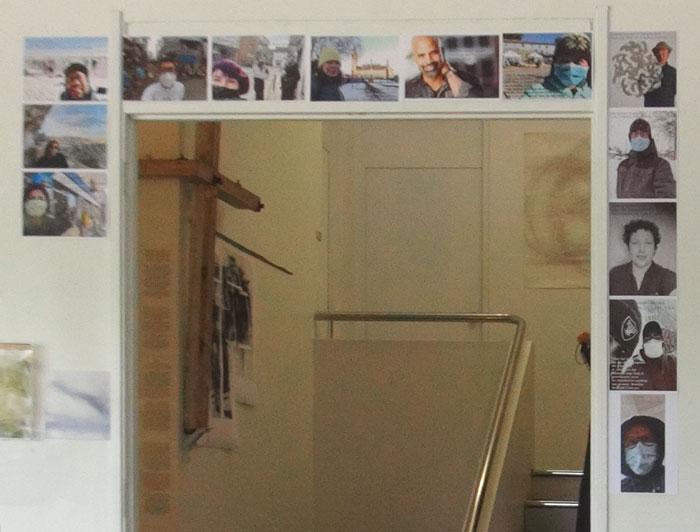

selfies from the other side – Aodhán Floyd, Chiara Rubino, Emma Papadopoulos, Jessy Rahman, Jumaadi, Lloyd Lawrence, Martin Wohlwend, Masud Olufani, Nawruz Paguidopon, Pietertje van Splunter, Robert Hamilton, Shaeron Caton Rose and Xiaojie Zheng

Details about each selfie is here: sonjavank.com/takecare/

The Wealth of the Nation, 2021, by Masud Olufani (Atalant, USA)

and Ursula Christel (Warkworth, NZ).

4-minute video, with accompanying text and a wall installation in the main gallery. Repurposed metal birdcage and brass bell, 2 framed digital prints, NZ native timber, cut and burnt copy of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (first published in 1776), twine, shellac. POA. The installation is a reinterpretation of The Wealth of the Nation (2019) by Masud Olufani; re-framed in New Zealand by Ursula Christel, in consultation with Masud.

Global Pandemic, 2021, by Robert Hamilton and Bev Goodwin 1 minute, 35 second video. Lightbox by Cathy Carter. Aus dem Gleichgewicht (Out of Balance), 2021, by Martin R. Wohlwend (Triesen, Liechtenstein) and Naomi Roche (Hamilton, NZ). Mats and carpets from artists’ homes. Windowsill sculptures: Kete I + Kete II by Ashleigh Taupaki (Auckland, NZ) and Shaeron Caton Rose (North Yorkshire, U.K). Mind That Māori suspended crochet vest by Lissy & Rudi Robinson. They are Minding their own Business, silkscreen on cloth by Sonja van Kerkhoff. Toro Mai Tō Ringa / Reach Out Your Hand, animation + wall sculpture by Nawruz Bernado Paguidopon (Manila, The Philippines) and Lissy & Rudi Robinson-Cole (Auckland, NZ).

The Wealth of the Nation, 2021, by Masud Olufani and Ursula Christel.

Detail: Rigenerazione by Chiara Rubino (Matera, Italy) and Cathy Carter (Auckland). Global Pandemic, 2021, by Robert Hamilton and Bev Goodwin 1 minute, 35 second video. Lightbox by Cathy Carter. Aus dem Gleichgewicht (Out of Balance) by Martin R. Wohlwend and Naomi Roche. Mats and carpets. Windowsill sculptures: Kete I + Kete II by Ashleigh Taupaki and Shaeron Caton Rose.

Transformazione, 2021, by Chiara Rubino (Italy) and Cathy Carter (Auckland). Archival pigment ink photographic print on Hahnemuhle photo rag 306gsm. 140cm x 90cm. Rigenerazione by Chiara Rubino and Cathy Carter. Global Pandemic by Robert Hamilton and Bev Goodwin. Lightbox by Cathy Carter. Aus dem Gleichgewicht (Out of Balance) by Martin R. Wohlwend and Naomi Roche. Windowsill: Kete I + Kete II by Ashleigh Taupaki and Shaeron Caton Rose.

Colour wheel, 2021, by Pietertje van Splunter. Acrylic paint on wood. Te Ara ki Rangihoua: The Way to Rangihoua (2018), by Yllwbro (NZ) and participating artists, five scallop shells. Care of the artists and Mokopopaki. Transformazione by Chiara Rubino and Cathy Carter.

Lissy writes Nawruz’s name. Te Ara ki Rangihoua: The Way to Rangihoua (2018) by Yllwbro (NZ) and participating artists.

– a scallop shell for each person, hung at their heart-height. With accompanying text elsewhere in the gallery. Lloyd Lawrence, NYC, U.S.A (153 cm), Shaeron Caton Rose, North Yorkshire, U.K (120 cm), Nawruz Paguidopon, Manila, The Philippines (127 cm), Xiaojie Zheng, San Francisco U.S.A. / Wenzhou, China (120 cm),

Robert Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, (150 cm).

Scallop shells, brown string, moko adhesive. Care of the artists and Mokopōpaki.

E-Motion (Kinetic series #1), 2021 by Phil Dadson, a response to Colour wheel, 2021, by Pietertje van Splunter (The Hague, The Netherlands, acrylic on wood -tree ring).

Acrylic on wood, motor/Arduino module, steel stand. The E-motion series is a spin-off from the June Music concept (2019), where ratios of frequency, rhythm and colour are conjured up from imagined lines of sonic shape and form in the material world. Like a breathing mandala, this first of the E–Motion series animates this idea from the 3rd to the 4th dimension.

(With thanks to James Charlton for motor/Arduino assistance).

The birth of Islam created a new space where non-Arabs and the lower strata of the tribes were included.

The Arabic text closest to the entrance to the first gallery of the Ko rātou, ko tātou | On other-ness, on us-ness exhibition (See details here or go to the blog introducing this exhibition) that was on show at NorthArt, Auckland, reads as “first house” (avvala baytin). Below this was the sentence from the Qur’an:

“Indeed, the first House [of worship] established for humanity was that at Makkah [Bakka] – blessed and a guidance for the worlds.”

The Qur’an, 3:96

Left to Right: Wave (detail), custom-made water tank by Jeff Thomson (link to a discussion of this work); Arabic text above reads: “first house (avvala baytin)”; Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level (2018) by Ursula Christel. Courtesy the artist and Mokopōpaki Acrylic, gesso, printed perspex, metal lugs, graphite, sealant on board (99 x 61cm), plastic spirit level (6 x 61cm);

Gavin Chilcott Pilgrimage to Mecca, 50 x 70 cm. Framed pastel on paper. Courtesy: John Perry.

Ever since the 1980s, when I first started reading about Islam, coming from a Roman Catholic background myself, I was struck by the concept of the qibla because while Rome is important, Catholics around the world, do not face a specific location while in prayer. The significance of this as I viewed it was that the Prophet Muhammad had envisioned a worldwide religion – of all cultures around the world facing the same location, as a daily sign of a shared global focus. Then while engaged in research for this exhibition I discovered that the text from the Qur’an refers to a change of direction, because previously the Prophet’s followers had faced Jerusalem when they prayed which was also the Jewish custom, and now they were to face Mecca (also known as Bakka or Bekka, the name of the area, or Makkah. See 2:144 which speaks of changing the qibla to Mecca).

For me as a Bahai, this brought in the concept of progressive revelation, the idea that all religions are the same religion (with the same God), and the variations are in relation to culture and history. So I saw the change as indicative of the evolution of Islam, even during the time of the Prophet Muhammad. It also explained for me why The Dome of the Rock built in Jerusalem in 691–92 at the order of Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik could have been built, although there is no clear record of its initial purpose. At the time, Jerusalem was a holy city for Jews and Christians. This building rivalled the Christian buildings, transforming the best aspects of current Byzantine architecture into a new form. The 1022-23 rebuilt Dome of the Rock has texts on the walls referring to Islamic teachings about Jesus. Today it is one of the oldest extant works of Islamic architecture, protects the rock believed to bear the imprint of the Prophet Muhammad’s foot, and is an icon and influence on Islamic architecture.

Foreground: New Space / Takawaenga, 2020, by Ursula Christel.

Left to Right: Wake, custom-made water tank, by Jeff Thomson; Arabic text reads: “first house”; Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level, 2018, by Ursula Christel. Courtesy the artist and Mokopōpaki; Pilgrimage to Mecca, 1986, by Gavin Chilcott.

Ursula Christel’s floor piece, made for this exhibition, New Space / Takawaenga, is the result of her research inspired by the concept of inclusion and the geometry of the floor plan of the Dome of the Rock. This Islamic holy place stands on a site that is sacred to Jews, Christians and Muslims – three of the Abrahamic religions.

Foreground: New Space / Takawaenga, 2020, by Ursula Christel.

Left to Right: Wake, custom-made silkscreened water tank, by Jeff Thomson; Arabic text “first house” (avvala baytin); Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level by Ursula Christel. Courtesy the artist and Mokopōpaki; Pilgrimage to Mecca by Gavin Chilcott; From the Eros and Psyche series (111), 1966/67, gouache on silk, by Joanna Margaret Paul, Courtesy M Paul;

two untitled corrugated iron sculptures by Jeff Thomson.

Like the Dome of the Rock, Christel’s, New Space / Takawaenga, is based on polygonal structures – of lines and repetitions of forms creating illusory space/s. Christel’s ‘new space’ is conceptualized not only in the multi-layered sight lines heading off at diverse angles across the space of the gallery but the stark checkered tiles also pull the eye to the pivot.

New Space / Takawaenga, 2020, by Ursula Christel. re-purposed wooden table (dia. 118 cm), 4 table legs (H: 46 cm), vinyl flooring, 3 mm acrylic sheets (83 x 83cm), glass chess board (38 x 38cm), ceramic tile (20 x 20cm), composite board (dia. 65cm), jute, LED lights.

The architectural references connect to her other work in the same gallery space, Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level, which also features circles within squares and vice versa.

This painting features a translucent image of her son who was born with Angelman syndrome, inside a circle superimposed over an image of Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man. Leonardo’s ‘ideal man’ is a faded shadow within a larger circle while Christel’s son sits up in a wheelchair with his arms held up and elbows bent outwards, a gesture that I — having met him a few times — recognize as meaning he is happy and excited.

Left to Right: Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level by Ursula Christel;

Pilgrimage to Mecca, 1986, by Gavin Chilcott.

On the wall opposite was Talking Sticks by Carolyn Lye and above another text in Arabic. This read: “Until you have asked permission”

Left to Right: The Prison of Self, 2015, by Sonja van Kerkhoff, 20 cm diameter, photographic print, texts in Persian, Māori and English, and oil-based varnish. Edition of 35. Text is from the Hidden Words by Baha’ullah, founder of the Bahai Faith; Text in Arabic reads: “Until you have asked permission,”; Talking Sticks, Korare stems, acrylic paint – 5 pieces, by Carolyn Lye.

Left to Right: The Prison of Self, by Sonja van Kerkhoff; Talking Sticks by Carolyn Lye; Conference of the Stones, 2013, video with soundscape by Phil Dadson (link to a discussion of this work); Detail of New Space / Takawaenga by Ursula Christel.

Left to Right: The Prison of Self by Sonja van Kerkhoff; Talking Sticks by Carolyn Lye; New Space / Takawaenga by Ursula Christel; Conference of the Stones by Phil Dadson.

The Māori title of Christel’s floorpiece, ‘Takawaenga’ (mediating/ed space/s), refers to a process. The work can also be read as an upside down table. A table that has been re-conceived in layerings, yet its circular form and central focus, created by the arrangement of the four legs, make it not a table but rather a direction for moving towards. In Sufi thought the lote tree of the outer limit (Sidrat al-Muntaha) marks the direction of all journeys. In choosing a circular table form and turning it over, the artist was inspired by George Dei’s words, “Inclusion is not bringing people into what already exists; it is making a new space, a better space for everyone.” 1

Left to Right: New Space / Takawaenga by Ursula Christel; Conference of the Stones by Phil Dadson; Peace Flight, 2011, giclée digital print by Brenda Liddiard. About her work >>

1. Dei, G.S.N. (2006). Meeting equity fair and square. Keynote address to the Leadership Conference of the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, September 28, 2006, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada.

About the 24 artists in the exhibition >>

Carolyn Lye, based near Karetu, Northland, Aotearoa | New Zealand, is a fibre artist who weaves and works in natural materials.

Gavin Chilcott, born in Auckland, Aotearoa | New Zealand, in 1950 and attended Auckland Technical Institute in 1967 followed by three years at Elam, School of Fine Arts, Auckland, from 1968-1970. His first exhibition was at the Barry Lett Gallery in 1976 and since then he has exhibited widely throughout New Zealand and Internationally. He has been a recipient of numerous Arts grants and is represented in all major New Zealand Collections.

Sonja van Kerkhoff, born 1960 in Hawera, Taranaki, Aotearoa | New Zealand, has a diploma in Fine Arts (1980-82, Otago School of Arts), dip Secondary Teaching (1986), Masters equivalent with a double major (1989-93, School of Fine Arts, Maastricht, The Netherlands) and a MSc in Media Technology (2005-8, University of Leiden, The Netherlands). She lives in Kawakawa, Northland, Aotearoa / New Zealand and The Hague, The Netherlands. sonjavank.com

Ursula Christel, born 1961 in Durban, South Africa, is of Celtic/ Germanic descent, immigrated to New Zealand in 1996. She has a BA Degree, majoring in Fine Art and Art History (1979 – 81) and a post grad Diploma in Education (1982). She is an artist, tutor, writer and disability advocate, and worked as a writer, editor and photographer for the Celebrate Art series of educational resources, featuring New Zealand and Australian artists.

These five blogs are an attempt to do some justice to, Ko rātou, ko tātou | On Other-ness, on us-ness, an exhibition that few individuals were able to see due to the gallery being closed because of COVID-19, on March 15, and from March 23 until mid May. The impetus for this exhibition, was my own experiences a year previously, following the Christchurch Mosque massacres. I realised how little experience many empathetic New Zealanders had of Islam. I am a Bahai, not a Muslim, but I have some insight into the diverse cultures of Islam because, over the decades, I, like many Bahais have engaged with Muslims and the Islamic worlds.

Detail of Huroof e Muqataat (The Disconnected Letters), chalk Arabic letters by Sen McGlinn on the inside of

Wake, corrugated iron water tank, by Jeff Thomson

Click for a larger view of this image.

Foreground: Wake, silkscreened corrugated iron water tank, by Jeff Thomson; New Space / Takawaenga, circular floorpiece, by Ursula Christel; Talking Sticks by Carolyn Lye;

Conference of Stones,

video and soundscape by Phil Dadson

Two texts in Arabic high on the walls read: ﯸ ﯷ (Until you have asked permission) and above the video: ةحال (The Stones)

Some of the works by 24 artists (listed here) were aesthetic responses to the 2019 Christchurch mosque massacres while others were re-contextualizations, or responses to the Qur’an and the diverse cultures and histories of Islamic worlds. A general aim here was to include Islam in a New Zealand aesthetic landscape, and to see what changes.

I will focus here on nine works in the show, and write separate blogs on the other works in the three gallery spaces.

The Arabic text above means “The Stones”

below detail of Conference of Stones,

video and soundscape by Phil Dadson

Photo: Ursula Christel

Click for a larger view.

Still: Conference of Stones, 2013, video and soundscape,

by Phil Dadson.

Filmed in HD 1920 x 1080 digital moving image, stereo recorded with Sennheisser microphones.

Credits:

Performed by Phil Dadson

Camera by Bruce Foster

Sound recorded by John Kim

Digital video/audio by Phil Dadson

Produced with the support of Pew Charitable Trust, CNZ Arts Council of New Zealand, Colab Creative Technologies,.

Watch an exceprt of this 3 screen video on vimeo.

Click for a larger view.

Conference of Stones, video and soundscape by Phil Dadson, Peace Flight, (far wall) Passion I and Passion III by Brenda Liddiard; A Matter of Faith, by Fiona Lee Graham; Kete Muka Tuatahi by Christina Hurihia Wirihana.

Click for a larger view.

Passion I and Passion III, 2010, Mixed media & collage on board, by Brenda Liddiard;

A Matter of Faith, 2020, monoprint, ink on paper, 150 x 100mm, by Fiona Lee Graham; Kete Muka Tuatahi by Christina Hurihia Wirihana.

Wake, silkscreened corrugated iron water tank,

by Jeff Thomson

The Arabic text on the wall beyond reads ‘The Heart’

Click for a larger view.

Detail of Huroof e Muqataat (The Disconnected Letters),

chalk Arabic letters by Sen McGlinn inside

Jeff Thomson’s water tank sculpture.

Detail of Huroof e Muqataat (The Disconnected Letters), chalk Arabic letters by Sen McGlinn

and Wake, corrugated iron water tank, by Jeff Thomson. Background: Conference of Stones, video and soundscape by Phil Dadson, Peace Flight, Passion I and Passion III by Brenda Liddiard;

A Matter of Faith, by Fiona Lee Graham;

About these 8 artists

Brenda Liddiard is a visual artist and singer songwriter/musician based in Auckland, Aotearoa | New Zealand. She has been exhibiting her paintings since 2008. brendaliddiard.co.nz, and is co-founder of the fundraising art organisation, Art for Change (www.artforchange.net).

Christina Hurihia Wirihana, based in the Bay of Plenty, Aotearoa | New Zealand, is a weaver of Te Arawa, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Rangiunora, Ngāti Raukawa, Tainui descent. Wirihana is the Chairperson of Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa (National Collective of Māori Weavers in New Zealand). In 2014 this collective of weavers exhibited 49 tukutuku panels in Kāhui Raranga: The Art of Tukutuku at Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. These panels are to be installed early 2015 at the Headquarters of the United Nations in New York. In 2003 Wirihana received Te Tohu Toi Kē from Te Waka Toi Creative New Zealand for making a positive development within Māori arts. See: wikipedia.org/wiki/Christina_Wirihana

Fiona Lee Graham, based in Auckland, completed a Bachelor Degree in Design and Visual Art, majoring in Painting, at the Unitec, Auckland, in 2010. See: thegreyplace.nz/artists/fiona-lee-graham

Jessika Kenney, based in Los Angeles, U.S.A. is an experimental vocalist, composer, and teacher. She is most known for her performances of Indonesian vocal music (sindhenan), and Persian vocal music (radifs), as well as for her compositions drawing on elements of both. See her discography – jessikakenney.com

Jeff Thomson based in Helensville, Aotearoa / New Zealand is known for his sculptures and site-specific installations using corrugated iron as his main medium. His sculptures range from the well-crafted and iconic, such as his suite of New Zealand native birds, to the conceptual, such as his cut and corrugated ironing boards, or the add-ons he created for the roofs of houses scattered throughout the city of Whanganui, to the quirky, such as his water tanks, some filled with water, peep holes and motors. jeffthomson.co.nz

Narjis Mirza, born in Pakistan and now based in Sydney, Australia, is an installation artist. Her research examines the confluence of eastern philosophy with virtual reality, highlighting the transcendent philosophy of Persian philosopher Mulla Sadra (1571–1636). She completed her Master’s degree in Media and Design from Bilkent University Ankara, Turkey, after a Bachelor’s in Fine Arts with distinction at the National College of Arts in Pakistan. She is currently undertaking a PhD at the Auckland University of Technology. narjismirza.com

Phil Dadson, based in Auckland, Aotearoa / New Zealand, is a video & sound artist with a transdisciplinary practice including building and performing with experimental musical instruments, sound sculptures, digital media, music compositions, graphic scores and drawings. Moving image and foregrounding sound has been a feature of his practice since the early 70s, referencing the body, land, nature, and the human condition. He also founded the music/performance group, From Scratch (1974 – 2004). Awards & residencies include: US Fulbright 1991, NZ Arts Foundation Artist Laureate 2001, Antarctic Artist Fellowship 2003, ONZM 2005, Sankriti residency (India 2007), Artist Cinema commission 2010, Wallace Arts Trust Jury award 2011. thearts.co.nz/artists/phil-dadson

Sen McGlinn, born in Christchurch, Aotearoa / New Zealand has recently returned to live in the Far North after living in the Netherlands for almost 30 years. He has a Master’s in Islamic Studies from the University of Leiden, The Netherlands, where he is working on a PhD. He has authored and co-authored a number of books in Persian Literature & Iranian Studies. He has exhibited in sculpture parks and galleries since the early 90s. sculpturebysen.wordpress.com

Ko rātou, ko tātou | On Other-ness, on us-ness

NorthArt, Northcote, Auckland, Aotearoa | New Zealand

curated by Salama Moata McNamara + Sonja van Kerkhoff

Open now until 31 May 2020

Artists will be at the gallery 12-3pm,

Sat., Sun., and Monday, 12-3, 23-25th May

Left to Right: Wave, custom-made water tank by Jeff Thomson

Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level by Ursula Christel. Courtesy the artist and Mokopōpaki

Pilgrimage to Mecca by Gavin Chilcott.

From the Eros and Psyche series (111) by Joanna Margaret Paul

Two untitled corrugated iron sculptures by Jeff Thomson

(foreground) New Space / Takawaenga (2020) re-purposed wooden table (dia. 118cm), 4 table legs (H: 46cm), vinyl flooring, 3mm acrylic sheets (83 x 83cm), glass chess board (38 x 38cm), ceramic tile (20 x 20cm), composite board (dia. 65cm), jute, LED lights by Ursula Christel.

New Space / Takawaenga is a conceptual assemblage inspired by geometry and the floor plan of the Dome of the Rock. It refers also to a quote by George Dei (2006) – “Inclusion is not bringing people into what already exists; it is making a new space, a better space for everyone.”

Takawaenga is a process. – Ursula Christel, 2020

Left to Right: Wave (detail), custom-made water tank by Jeff Thomson

Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level (2018) by Ursula Christel. Courtesy the artist and Mokopōpaki Acrylic, gesso, printed perspex, metal lugs, pencil, sealant on board (99 x 61cm), plastic spirit level

(6 x 61cm). Gavin Chilcott Pilgrimage to Mecca Framed pastel on paper.

Arabic text above reads: “first house (avvala baytin)” A4 text below this begins with:

“Indeed, the first House [of worship] established for humanity was that at Makkah

– blessed and a guidance for the worlds”. The Qur’an, 3:96

This is one of 5 texts in Arabic arranged around the first gallery.

More about these texts and the works in the next blog.

still: “Haykal Al Noor” (Bodies of Light), site specific video installation by Narjis Mirza

with the soundscape, “Pamor” by Jessika Kenney

in this short video on youtube which also shows these works:

“Light District,” framed canvas, LED lighting, by John Mulholland;

“Halg” (Throat) video from the series Sokout/Silence, by Azadeh Emadi;

“Ka aroha” (Love), gouache and ink on paper,

by Salama McNamara & Emma Paton;

“Auckland Flowers 15/03/2019,” dried flowers, soil, compost, brown paper, by Java Bentley;

“Love is Blind,” embossed braille on paper,

by Tash Nikora;

“Fabric of Humanity” cast glass with impressions of a hijab pattern based on the hijab worn by New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern in 2019 by Layla Walter;

“Fifty-one” an installation incorporating an assemblage of painted stacked cards and texts from Rumi by Michelle Mayn.

Some photos of the exhibition are here: artsdiary.co.nz

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.