The birth of Islam created a new space where non-Arabs and the lower strata of the tribes were included.

The Arabic text closest to the entrance to the first gallery of the Ko rātou, ko tātou | On other-ness, on us-ness exhibition (See details here or go to the blog introducing this exhibition) that was on show at NorthArt, Auckland, reads as “first house” (avvala baytin). Below this was the sentence from the Qur’an:

“Indeed, the first House [of worship] established for humanity was that at Makkah [Bakka] – blessed and a guidance for the worlds.”

The Qur’an, 3:96

Left to Right: Wave (detail), custom-made water tank by Jeff Thomson (link to a discussion of this work); Arabic text above reads: “first house (avvala baytin)”; Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level (2018) by Ursula Christel. Courtesy the artist and Mokopōpaki Acrylic, gesso, printed perspex, metal lugs, graphite, sealant on board (99 x 61cm), plastic spirit level (6 x 61cm);

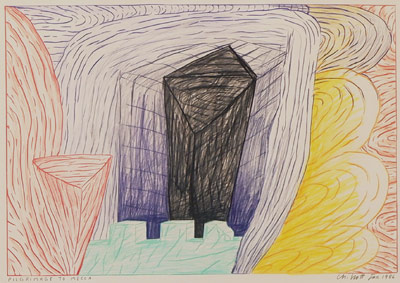

Gavin Chilcott Pilgrimage to Mecca, 50 x 70 cm. Framed pastel on paper. Courtesy: John Perry.

Ever since the 1980s, when I first started reading about Islam, coming from a Roman Catholic background myself, I was struck by the concept of the qibla because while Rome is important, Catholics around the world, do not face a specific location while in prayer. The significance of this as I viewed it was that the Prophet Muhammad had envisioned a worldwide religion – of all cultures around the world facing the same location, as a daily sign of a shared global focus. Then while engaged in research for this exhibition I discovered that the text from the Qur’an refers to a change of direction, because previously the Prophet’s followers had faced Jerusalem when they prayed which was also the Jewish custom, and now they were to face Mecca (also known as Bakka or Bekka, the name of the area, or Makkah. See 2:144 which speaks of changing the qibla to Mecca).

For me as a Bahai, this brought in the concept of progressive revelation, the idea that all religions are the same religion (with the same God), and the variations are in relation to culture and history. So I saw the change as indicative of the evolution of Islam, even during the time of the Prophet Muhammad. It also explained for me why The Dome of the Rock built in Jerusalem in 691–92 at the order of Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik could have been built, although there is no clear record of its initial purpose. At the time, Jerusalem was a holy city for Jews and Christians. This building rivalled the Christian buildings, transforming the best aspects of current Byzantine architecture into a new form. The 1022-23 rebuilt Dome of the Rock has texts on the walls referring to Islamic teachings about Jesus. Today it is one of the oldest extant works of Islamic architecture, protects the rock believed to bear the imprint of the Prophet Muhammad’s foot, and is an icon and influence on Islamic architecture.

Foreground: New Space / Takawaenga, 2020, by Ursula Christel.

Left to Right: Wake, custom-made water tank, by Jeff Thomson; Arabic text reads: “first house”; Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level, 2018, by Ursula Christel. Courtesy the artist and Mokopōpaki; Pilgrimage to Mecca, 1986, by Gavin Chilcott.

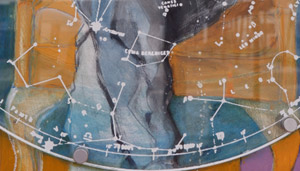

Ursula Christel’s floor piece, made for this exhibition, New Space / Takawaenga, is the result of her research inspired by the concept of inclusion and the geometry of the floor plan of the Dome of the Rock. This Islamic holy place stands on a site that is sacred to Jews, Christians and Muslims – three of the Abrahamic religions.

Foreground: New Space / Takawaenga, 2020, by Ursula Christel.

Left to Right: Wake, custom-made silkscreened water tank, by Jeff Thomson; Arabic text “first house” (avvala baytin); Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level by Ursula Christel. Courtesy the artist and Mokopōpaki; Pilgrimage to Mecca by Gavin Chilcott; From the Eros and Psyche series (111), 1966/67, gouache on silk, by Joanna Margaret Paul, Courtesy M Paul;

two untitled corrugated iron sculptures by Jeff Thomson.

Like the Dome of the Rock, Christel’s, New Space / Takawaenga, is based on polygonal structures – of lines and repetitions of forms creating illusory space/s. Christel’s ‘new space’ is conceptualized not only in the multi-layered sight lines heading off at diverse angles across the space of the gallery but the stark checkered tiles also pull the eye to the pivot.

New Space / Takawaenga, 2020, by Ursula Christel. re-purposed wooden table (dia. 118 cm), 4 table legs (H: 46 cm), vinyl flooring, 3 mm acrylic sheets (83 x 83cm), glass chess board (38 x 38cm), ceramic tile (20 x 20cm), composite board (dia. 65cm), jute, LED lights.

The architectural references connect to her other work in the same gallery space, Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level, which also features circles within squares and vice versa.

This painting features a translucent image of her son who was born with Angelman syndrome, inside a circle superimposed over an image of Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man. Leonardo’s ‘ideal man’ is a faded shadow within a larger circle while Christel’s son sits up in a wheelchair with his arms held up and elbows bent outwards, a gesture that I — having met him a few times — recognize as meaning he is happy and excited.One of the wheels rests on the outer of the two circles as if to demonstrate that the circle around him is a bubble that moves with him. That this is his world, who he is, and he belongs. This repudiates the idea of the ideal human in Leonardo’s image. Both images of the self utilize the circle to symbolize one’s reach – one’s place in the cosmos.

Left to Right: Vitruvian Angel Man with Spirit Level by Ursula Christel;

Pilgrimage to Mecca, 1986, by Gavin Chilcott.

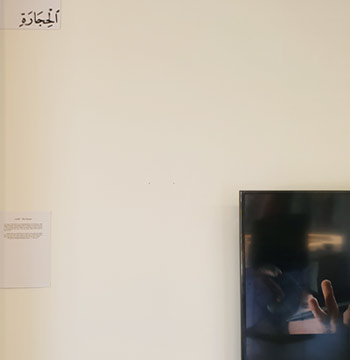

On the wall opposite was Talking Sticks by Carolyn Lye and above another text in Arabic. This read: “Until you have asked permission”

Left to Right: The Prison of Self, 2015, by Sonja van Kerkhoff, 20 cm diameter, photographic print, texts in Persian, Māori and English, and oil-based varnish. Edition of 35. Text is from the Hidden Words by Baha’ullah, founder of the Bahai Faith; Text in Arabic reads: “Until you have asked permission,”; Talking Sticks, Korare stems, acrylic paint – 5 pieces, by Carolyn Lye.

Left to Right: The Prison of Self, by Sonja van Kerkhoff; Talking Sticks by Carolyn Lye; Conference of the Stones, 2013, video with soundscape by Phil Dadson (link to a discussion of this work); Detail of New Space / Takawaenga by Ursula Christel.

I associated the Arabic text to two loose ideas – the Middle Eastern Islamic practice of distinguishing or dividing between inner and outer domestic spaces and the use of the word ‘hejab’ which means screen and is the same word used for the headscarf. I placed two works nearby which I felt related aesthetically to this Middle Eastern Islamic sense of the protected space.

Lye’s, Talking Sticks were arranged to create a ‘space’ behind them as well linking them to architecture of the gallery space. The second work, the circular “Prison of Self” by myself, shows text in Persian, English and Māori. It is a Bahai text, not Islamic, but Islamicate (from the space/s of an Islamic world). A translucent veil pierced by Persian text hangs like a screen in the photograph collage.

Left to Right: The Prison of Self by Sonja van Kerkhoff; Talking Sticks by Carolyn Lye; New Space / Takawaenga by Ursula Christel; Conference of the Stones by Phil Dadson.

Religions almost always involve the differentiation of space and meaning into the inner and outer, sacred and profane, referential and literal. The four works in this corner of the gallery, for me, are explorations of this theme of the differentiation of space and meaning in relation to Islam. In the video soundpiece, Conference of the Stones by Phil Dadson, profane stones are charged by action into a meditation or an invocation of the spirit.

The Māori title of Christel’s floorpiece, ‘Takawaenga’ (mediating/ed space/s), refers to a process. The work can also be read as an upside down table. A table that has been re-conceived in layerings, yet its circular form and central focus, created by the arrangement of the four legs, make it not a table but rather a direction for moving towards. In Sufi thought the lote tree of the outer limit (Sidrat al-Muntaha) marks the direction of all journeys. In choosing a circular table form and turning it over, the artist was inspired by George Dei’s words, “Inclusion is not bringing people into what already exists; it is making a new space, a better space for everyone.” 1

Left to Right: New Space / Takawaenga by Ursula Christel; Conference of the Stones by Phil Dadson; Peace Flight, 2011, giclée digital print by Brenda Liddiard. About her work >>

1. Dei, G.S.N. (2006). Meeting equity fair and square. Keynote address to the Leadership Conference of the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, September 28, 2006, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada.

About the 24 artists in the exhibition >>

Carolyn Lye, based near Karetu, Northland, Aotearoa | New Zealand, is a fibre artist who weaves and works in natural materials.

Gavin Chilcott, born in Auckland, Aotearoa | New Zealand, in 1950 and attended Auckland Technical Institute in 1967 followed by three years at Elam, School of Fine Arts, Auckland, from 1968-1970. His first exhibition was at the Barry Lett Gallery in 1976 and since then he has exhibited widely throughout New Zealand and Internationally. He has been a recipient of numerous Arts grants and is represented in all major New Zealand Collections.

Sonja van Kerkhoff, born 1960 in Hawera, Taranaki, Aotearoa | New Zealand, has a diploma in Fine Arts (1980-82, Otago School of Arts), dip Secondary Teaching (1986), Masters equivalent with a double major (1989-93, School of Fine Arts, Maastricht, The Netherlands) and a MSc in Media Technology (2005-8, University of Leiden, The Netherlands). She lives in Kawakawa, Northland, Aotearoa / New Zealand and The Hague, The Netherlands. sonjavank.com

Ursula Christel, born 1961 in Durban, South Africa, is of Celtic/ Germanic descent, immigrated to New Zealand in 1996. She has a BA Degree, majoring in Fine Art and Art History (1979 – 81) and a post grad Diploma in Education (1982). She is an artist, tutor, writer and disability advocate, and worked as a writer, editor and photographer for the Celebrate Art series of educational resources, featuring New Zealand and Australian artists.